Zack Smith's "Exit Stage Right" Show Starts a Conversation on Portraits

Why Are We Building Such a Big Ship? by Zack Smith at Chaz Fest 2007

The New Orleans photographer’s show at The New Orleans Jazz Museum documents a who’s who in the music community a decade ago, but it also does a lot more.

Photographer Zack Smith sent me some of the images from “Exit Stage Right: Zack’s Smith’s Festival Portraits,” his new show now on display in The New Orleans Jazz Museum. The individual photos of musicians taken backstage at music festivals in the 2000s are compelling on their own, but they’re best viewed as presented on the walls in the gallery in large groupings.

The concept behind his adventure in portraiture began from a documentary impulse as he wanted a record of the people who made New Orleans’ music scenes happen—not just the musicians but the fans and the people who worked in the industry around them. Smith’s impulse was also expansive as he focused as much if not more attention on the indie community as headliners at the House of Blues and Tipitina’s. Because his work started with that conceptual groundwork, his photos need to be seen in groupings on the way because really, he shot communities. Seeing members of the Noisician Coalition next to Rosie Ledet—who could clearly only imagine posing in publicity shot ways—next to Uncle Lionel Batiste uncharacteristically wearing a T-shirt next to Anders Osborne at his most mountain man tells a better story than each of the photos individually. Those photos subtly make a case for part of what makes New Orleans’ music community special when these people coexist in the same space and are equally meritorious of a photographer’s attention.

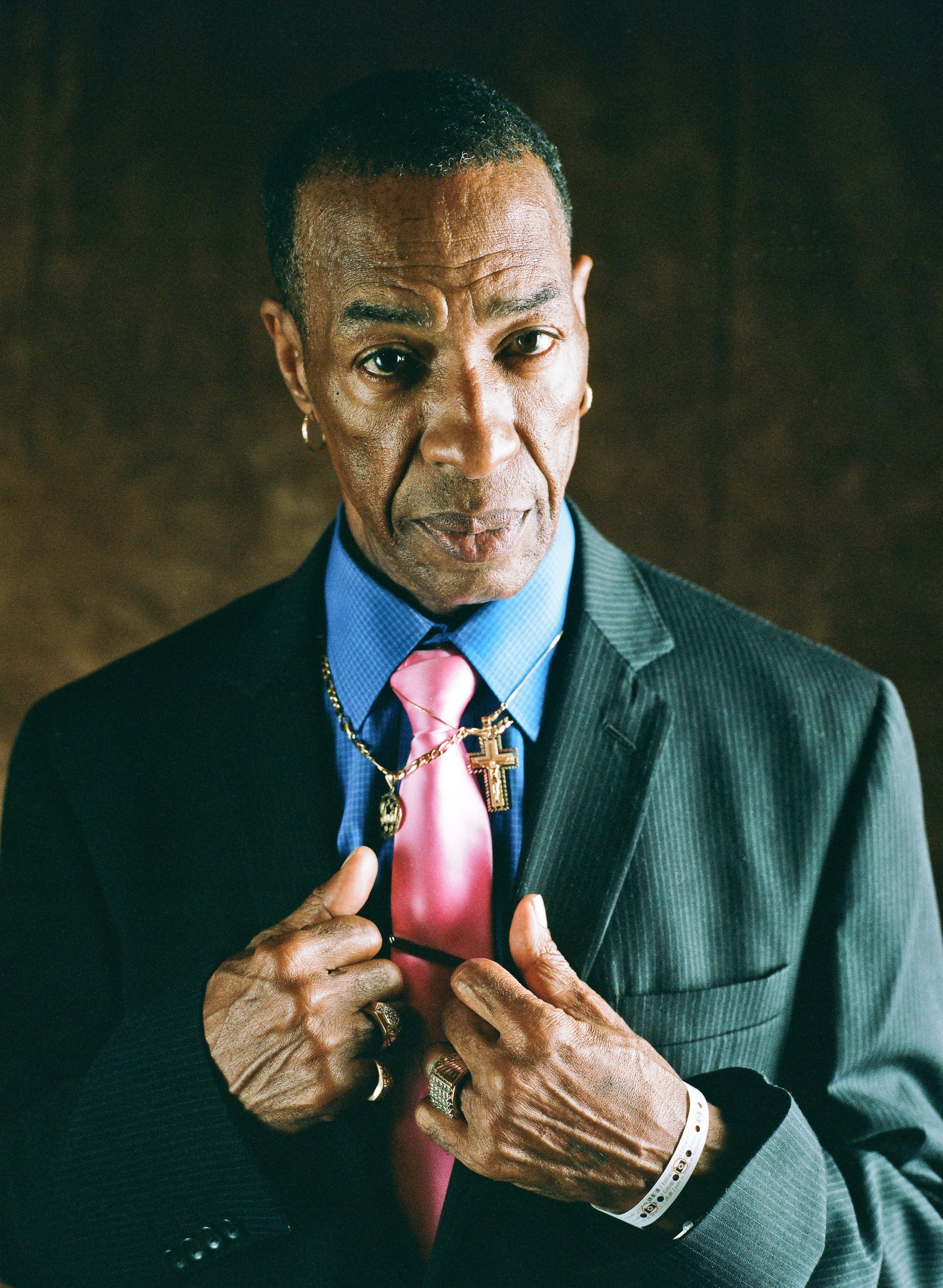

David Batiste by Zack Smith at Ponderosa Stomp 2013

To get these photos, Smith made arrangements with the producers of festivals in the area to set up his version of a photo booth just off stage, so when talent finished playing, he could grab them and get a series of shots before turning them loose. The set-ups were usually makeshift, whether with improvised props and furnishings. In one series of portraits not represented here, he outfitted an old medicine chest with neon lights to hyper-light his subjects, and he often used a sheet of plywood on a couple of sawhorses to keep his cameras off the ground. The height of luxury came one year when Preservation Hall and Flavor Paper got together to make wallpaper that would serve as a backdrop for Smith’s photos from Voodoo. He usually took a limited number of shots with minimal instructions and let creative people do creative things for his camera. Rarely do people simply smile in these shots, and because of that, his portraits look true to his subjects. Paul Sanchez looks like himself and not an edited, packaged version ready to be sold to record labels.

At the same time, Smith’s hand as an artist is light. Portraits often invite viewers to consider the relationship between the photographer and the subject, but perhaps because Smith’s set-up is semi-mechanical and part of a process, he doesn’t lurk just outside the frames of his shots. His portraits stand alone and with their peers, but not as a stand-in for him.

View “Exit Stage Right” as Smith imagined the photos in the first place—as documentation—and you see a moment in time. That’s probably the least compelling way to think about the show because that likely only means much if you were around at the time or are around New Orleans’ music business now. Want to know why somebody is a player? The answer might be on the wall, but because of Smith’s aesthetic and at times access, his show isn’t a portrait gallery of the city’s biggest stars, and if you’re new-ish to the city, a lot of the faces will mean nothing.

Odoms and Ballzack by Zack Smith at Voodoo 2008

If that’s you though, Smith’s show presents a different thought exercise. Look at his portraits and think about what these people are doing now. You know some of them have to be dead. Not everybody looks like a star, so you know some of them aren’t in the game anymore. Look at those with the most charisma and think about their moment. Did they have one? If they did, what was it like? Smith’s success at capturing his subjects’ humanity makes speculation into the lives behind the images not only a valid approach but a necessary one.

His portraits almost demand that response because many of his subjects appear to be having a great day when they’re in front of his camera. The shots from Chaz Fest feel like they came from a triumphant moment because for many of them, they did. The Bywater festival featuring acts overlooked by Jazz Fest drew such an enthusiastic mix of locals and out-ot-towners that it felt like the aesthetics on display were the ones that won, and that for at least a day, the Truck Farm was the musical center of New Orleans.

That excitement and sense of possibility is the live wire that runs through “Exit Stage Right,” as you can see Smith’s subjects posing for futures they hoped to have as well as presents that were more exciting than they had imagined. He frequently shot people together, and in those portraits you get clues as to how their lives were led.

Zoom out and you see what portraits have come to mean in contemporary pop culture. From Hollywood to Warhol to Annie Leibovitz to Anton Corbijn and beyond, the portrait has been one of the trappings of stardom, and in Smith’s portraits in “Exit Stage Right,” you can see his subjects living that celebrity moment their ways. What they did with that moment is the story behind the show.

I also wrote about Smith’s portrait work in 2013.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.