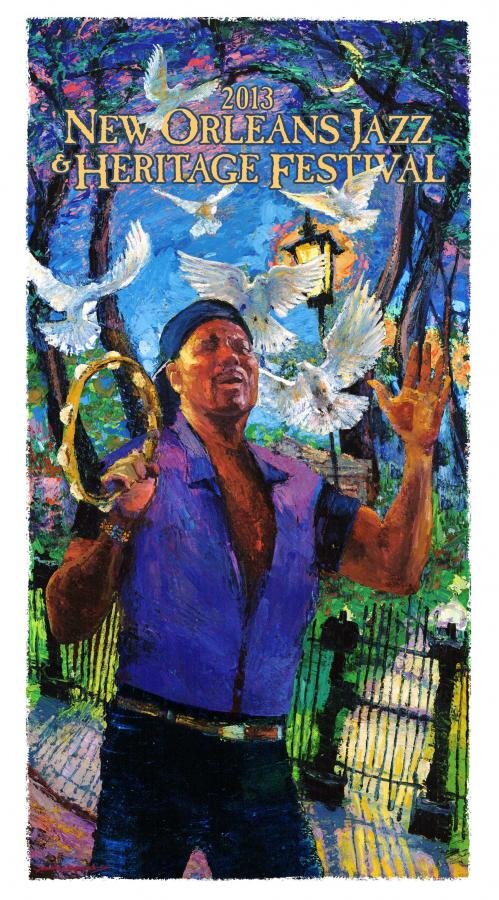

Kid Ory a Newspaper Man's Challenge

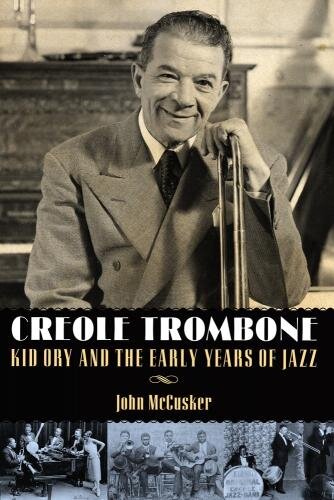

Former T-P photographer John McCusker digs in to the documents to tell Kid Ory's story.

McCusker will sign and read from Creole Trombone tonight at 6 p.m. at Octavia Books, and while many creative projects drift into existence, his has a very specific origin moment. After one of his tours, a teacher from California objected to his characterization of Ory as primarily a side man for Louis Armstrong, King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton. It was the history that was being told at the time, but his Californian argued that Ory was far more important than that, that he bridged two generations of jazz, overlapping with Buddy Bolden and Louis Armstrong. That challenge sent McCusker to Bruce Raeburn of the Tulane Jazz Archive to discuss Ory’s place in the jazz world. He agreed with the Californian, then started McCusker researching Ory.

“He said there was a controversy about [Ory's] birthday, that a recent academic had written and hypothesized that Ory was actually born in 1889, not 1886,” McCusker says. “I figured, ‘I’m a journalist; I can solve this puzzle.’ My first staffing at the Picayune was in the River Parishes Bureau, in LaPlace. I knew what church Ory would have gone to. I wrote away to the Archdiocese, and a week and a half later I had Ory’s baptismal certificate, proving that he was, in fact, born in 1886.” When he returned Raeburn with his findings, Raeburn pointed out that no biography of Ory existed, starting McCusker on the road to Creole Trombone.

Research for the book was similarly methodical as he spent from 1994 to 2000 collecting all the documentation he could on Ory, and he did his genealogy back to 1702. He then found Ory’s daughter Babette, who still had her father’s unpublished “autobiography” - more a series of memories and reflections on loose sheets a paper than a coherent narrative. His own research told him it was less than authoritative as a source of fact because some stories couldn’t have happened in the sequence presented in Ory’s writing, and because his second wife, Barbara GaNung, inserted herself into the process.

“Ory dictated this to his then-mistress, who is Babette’s mom. Barbara GaNung,” McCusker says. “She wrote it in shorthand, so that’s useless to me. She would then transcribe each story out individually. That’s what I call version two. Then at some point, she takes these stories from version two, along with some other material, and tries to write a cohesive narrative, putting it all together. This is where the problem came in. When I was able to compare the stuff in that, the way that she wrote it in this so-called cohesive narrative, with the timeline I had, it showed that she had made the whole thing up. The stories were true, but the segue narratives between each story were not. I was able to redact her out of it. Also, she had some agendas. You could see that where Ory would use a one-dollar word to say something, suddenly this five-dollar word shows up and you know that’s not Ory. She had an agenda about race, too. Whereas in one story he talks about going into this bar and seeing this nice, brown-skinned looking girl, by the third edition, it’s a nice-looking girl. But after reading the documents enough times, it wasn’t hard to go in and figure out what was her and what was Ory.”

Creole Trombone takes place in a very different New Orleans, one that is connected by train to Carrollton and the Lakefront, communities that were destinations with their own nightspots and social centers. Because Ory played Storyville, McCusker examines it as part of his milieu, and presents a more nuanced vision of it as a place with its own internal dividing lines between classier and less classy parts of the District. Ory’s autobiography wasn’t reliable as a document of fact, but it did give McCusker access to his voice, including his thoughts on Storyville:

I was nothing but a boy from the country, living a clean life while I was growing up, not knowing what was going on in the world, but I want to thank New Orleans and Storyville for opening my eyes to how the rest of the world lived and how people enjoyed themselves in that tough life. It looked as if the people were much happier down there doing the things they did; which we would call wrong; more so than people of today having a good time and leading a clean life.

The material on Storyville was news to McCusker, as was much of what he found researching the book, and it affected the way he thinks of the city.

“When I drive around New Orleans now, I don’t just see the New Orleans that’s there now,” he says. “I picture what was there then, and I really tried to give a sense of the geography as much as I could when writing it, about how different the city was then.”

Updated October 10, 7:50 a.m.

The live streaming player has been replaced with a video of last night's talk by McCusker. To test the video feed, we started rolling before McCusker speaks. You can watch him sign books and talk to people, or you can skip forward to the 11:15 mark when Octavia Books' Tom Lowenburg introduce me, but the feed is pretty rugged. At 13:40, McCusker starts and the video solidifies. It's not the same as being there, but McCusker gave a very animated, entertaining talk on the story behind Creole Trombone that's well worth hearing. My apologies to those who tried unsuccessfully to watch last night. A bad embed code meant that I had the wrong player up for part of his talk.

Updated October 11, 12:32 p.m.

The video has been edited to cut off the first 10 minutes of signings.