New Orleans Musicians Show Love and Support for Lil' Queenie

A Thursday night tribute to Leigh "Lil' Queenie" Harris will benefit the singer's cancer treatment.

For season one of HBO’s Treme, music supervisor Blake Leyh wanted to include a performance by Lil’ Queenie, but the show aimed for chronological accuracy and she wasn’t in New Orleans when the series’ story started in late 2005. Leigh “Lil’ Queenie” Harris had been a talent big enough to be known solely by her nickname before Katrina, but since she never moved back after evacuating, her voice and presence has been absent from the new New Orleans.

Because she never moved back, social media didn’t blow up like otherwise might have at the announcement that she has cancer—Stage IV breast cancer that has metasticized. In April, Harris revealed the news when her sister convinced her to launch a GoFundMe page to help with the expenses of medical treatment—something she agreed to only reluctantly. “Anyone who knows me is probably familiar with the difficulty of trying to wrestle a heavy bag away from me, and this might be the weightiest bag I've had to carry to date,” she wrote on the page.

So far, friends and well-wishers have contributed more than $22,000, and when singer Debbie Davis told Snug Harbor musical director Jason Patterson about Harris’ condition, he asked, We’re doing a benefit, right?

“Gawd Save the Queen” takes place Thursday night at Snug Harbor with two shows at 8 and 10, and Davis encountered similar enthusiasm from musicians eager to do what they can for Harris. The show already includes Davis, Susan Cowsill, Vicki Peterson, Darcy Malone, Suzy Malone, Holley Bendtsen, Yvette Voelker, Josh Paxton, Andre Bohren, Matt Perrine, Jimmy Robinson, Cranston Clements, Tom Marron, Peter Holsapple, and Spencer Bohren, and others have approached Davis about being involved. All shared the stage with Harris at one point or another, and the show will be about Harris and their musical relationships with her.

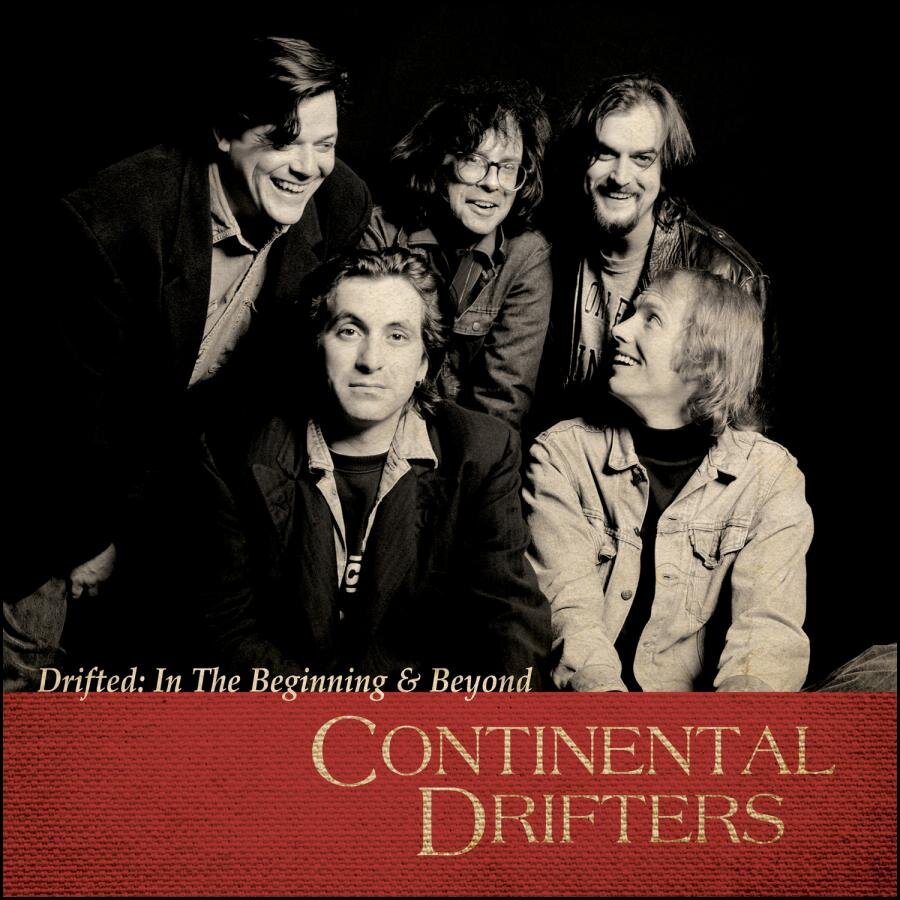

Harris grew up in Old Metairie and started playing in 1977 with Lil Queenie and The Percolators—her band with pre-subdudes John Magnie and Tommy Malone. They blended rock and R&B, and Harris brought a powerful, soulful voice, charisma, and some of the edgy style of the day. The band's biggest release was the 45 “My Darlin’ New Orleans,” which Treme honored by including it in the show’s soundtrack, placing it on the Treme’s soundtrack album, and naming its fundraising event series for local non-profits “My Darlin’ New Orleans.”

After the Percolators split in 1982, Harris continued to perform on her own and with new bands. Holsapple was in one, The Mixed Knots, and he told Michael Hewlett of the Winston-Salem Journal, “She is so highly regarded as a singer and a spiritual figurehead. She's able to gather people from all walks of life. She's gotten to draw in the finest talent New Orleans has to offer, not to mention the rest of the world.” Harris now lives in North Carolina.

For Debbie Davis, organizing the tribute has been a professional courtesy, to say the least. Harris’ career and artistic choices helped pave the way for many of the female singers in New Orleans today. Genre-crossing female vocalists were far less common before Harris in New Orleans if not the country. John Magnie remembered a New York Times review from 1980 to Nola.com’s Doug MacCash:

The next day we saw this article in The New York Times that compared Leigh to Janis Joplin, which was something she really didn't appreciate. She had all the charisma and bad habits of Janis Joplin, but felt she was a more nuanced singer. It was a totally supportive, glowing article. I was really validated. I always thought she was something special.

Davis thinks she was the first white female singer in New Orleans to be legendary, someone everybody knew simply as Lil’ Queenie the way everybody knew Mac Rebennack as Dr. John. “You don’t have to know her real name to know who she is,” Davis says. “She’s one of those larger than life legacies.

“A lot of singers owe her a debt of gratitude. They were influenced by her even if they don’t know why. She was so capable of inventing herself and reinventing herself. There was no difference for her between Diana Washington and Prince, and the crossover between genres was natural for her. The fearlessness with which she approached music was very appealing.”

But their relationship goes deeper than that. “When I moved to New Orleans, she was maybe the first real friend I had here,” Davis says. She moved to New Orleans in 1997, and Matt Perrine was playing bass with Harris at the time. The first time Davis met Harris, Perrine introduced them and before the night was over, the two were drinking at the bar like they’d known each other for years. Davis and Perrine moved out of their French Quarter apartment when Harris insisted that they move into the vacant apartment upstairs from her. “We were her upstairs neighbors for three years. She was like family. We had meals together. We had coffee together in the morning and cocktails at night.” As their relationship grew professionally as well as personally, Harris introduced Davis to members of the city’s musical community.

“She gave me the gift of all these relationships with all these other amazing people who I have so much love and affection for,” Davis says.

Organizing a benefit not only gave Davis a way to help Harris, but a way to help herself.

“It brings some sort of emotional catharsis,” she says, and being with others who share her pain and anxiety is therapeutic as well. “Just being around people who feel the same kind of pain in their hearts to know that she’s sick, that in itself is not just dealing with it but a means by which to heal.”