Orpheus in the Moment

Panther Burns' Tav Falco's vision takes a little explaining, but his photos, films, book and music share it.

Tav Falco's deceptive vision is on display in photos, films and music the Ogden this weekend.

Tav Falco sent this message to further a conversation we’d had the day before about his art, which has never been easy to pin down. It’s all on display this week at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art - his short films (Thursday night), his band Panther Burns (Friday night) and his photography (which opens Saturday night with Art for Art’s Sake). He also has a new book, Ghosts Behind the Sun: Splendor, Enigma & Death, a dense, highly personalized history of Memphis from the city’s origins to the underground scene that spawned him in the late 1970s.

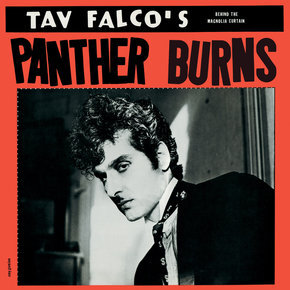

Ghosts Behind the Sun bring to mind my first experience with Panther Burns, not because it’s a musical book but because it prompts the same questions. 1980’s Behind the Magnolia Curtain treats all musical verities as options as the band chugged through a series of obscure country, rockabilly and rock ‘n’ roll covers. Consistent tempo - do we have to? In tune? In key? Together? How together’s together?

In his book, he recounts an appearance by Panther Burns on a Memphis morning television program:

“Tell me Gustavo, what are you on?”

“I’m not on anything!” Falco proclaimed. “I’m just on KHBQ at nine o’clock in the morning.”

Yes, he refers to himself in the third person in the book as his narrator shifts through a host of identities, part of the Panther Burns periphery being only one of them. It’s confusing at times, and the story slows down for digressions and fascinations, so much so that it’s easy to wonder if he’s lost control in the same way that Behind the Magnolia Curtain prompted concerns about musicianship. But in each case, he committed so thoroughly to what he was doing, control was beside the point. And as he says, his vision is sometimes playful and not without irony.

He moved from Arkansas to Memphis, and accounts of his time there raise the possibility that his real art work is his life - an extremely extended performance piece with a host of semi-confrontational manifestations. Chainsawing a guitar while singing Leadbelly’s “Bourgeois Blues.” Performing in a silver trash bag tied at the waist with a sash. When rock ‘n’ roll audiences thought they got him, he moved to Vienna and embraced the tango. It had always been part of his music, but the gentleman tango dancer and not the thinking man’s rockabilly guy became the identity he forced people to add to their mental Falco scoresheet. Was his tango ironic? Who knew enough about tangos to know?

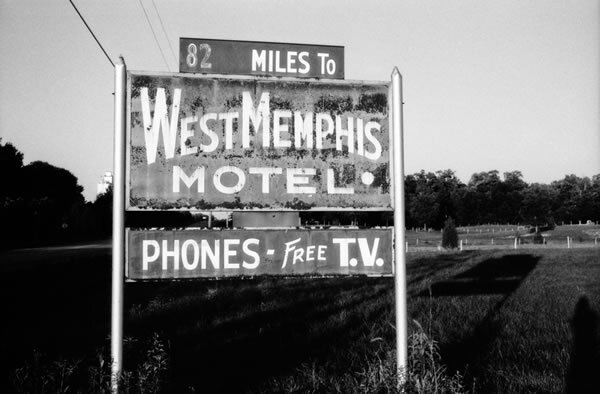

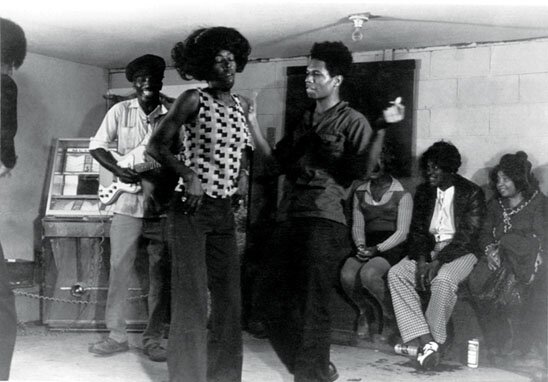

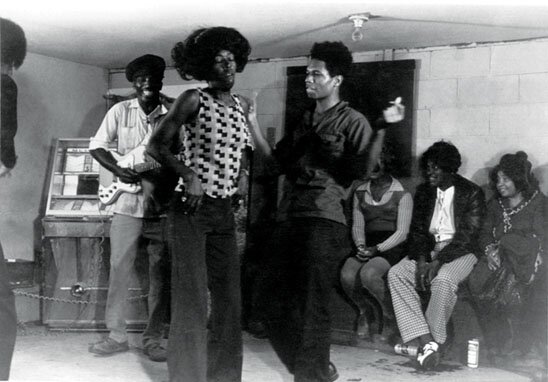

By the time I saw Panther Burns in Toronto in 1981, word of his photography had got around and clued the curious that there was more to the noise than noise. He’d developed film for William Eggleston, and many of his photos shared Eggleston’s deadpan treatment of unconsidered spaces, but he also applied a similar visual voice to photos of people on the scene. It’s not loving nor even affectionate, but it’s not completely dispassionate either. That stance is one thing when taken with signs, buildings and storefronts, but it’s more complicated when taken with real people. His portraits are just engaged enough that you see the subject’s efforts to be beautiful, to be handsome, to be funny or to be cool, and you want his camera to love them more - or at least respond to them more clearly.

The moment vs. mediation - that tension’s at the heart of all of Falco’s work. Panther Burns loves rock ‘n’ roll but shows it in funny ways. His book’s a love letter to Memphis written in a forgotten language. He’s a Renaissance Man who leaves you wondering what he’s good at.

Tomorrow: An interview with Tav Falco