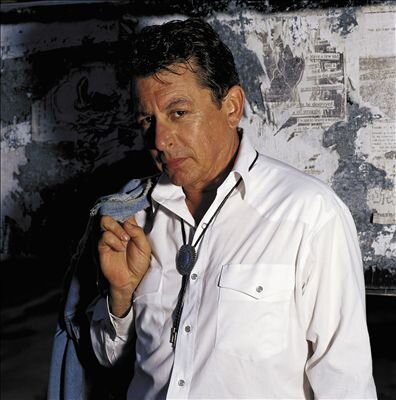

Panhandle Rambler Joe Ely Remembers Rambling

The Texas country/folk/rock singer talks about how hard it is to live off the land today.

Today, I talk with Joe Ely about his rambling days in The New Orleans Advocate before he plays Chickie Wah Wah Saturday night in support of his recent album, Panhandle Rambler. A few years ago, I interviewed the Texas country/folk/rock singer for The Oxford American about his relationship with The Clash, including touring Texas with them on their first American tour. This time, we talked about his freight-hopping days, doing whatever he could to see the world beyond the Lubbock city limits.

There was more in the conversation than fit in the Advocate story, so here he is talking about how much harder it is to pick up and go without a car or money today than it was for him in the 1960s.

When I was a kid, I traveled around jumping freight trains, playing guitar on street corners. We’d jump trains and go from West Texas to Southern California right across the desert.

The interstates have made it impossible to hitchhike across country anymore. If you take the back roads, you’re pretty much sure to get stuck for days at a time in places you don’t want to be, and the interstates are patrolled and don’t let hitchhikers or bicyclists on the interstates. And since 9/11, I’ve noticed that the boxcar doors on trains are always sealed shut. Before 9/11, almost all the trains had wide open boxcars that you could catch pretty easy. All of that’s changed, and it’s harder for people to roam freely anymore.

In the interview, Ely said, ““Growing up in the ’60s learning Woody Guthrie songs and reading Jack Kerouac books, there was a certain kind of adventure to plug into. And you kind of had to be homeless in order to be able to pick up and go in any direction at any time. You hear about things and pack up and go to them without a second thought.”

After a previous show at Chickie Wah Wah, a fan gave Ely a sign that a homeless person used to raise money. I asked him about that.

About 10 years ago, I started seeing them everywhere and became real curious about them. Instead of giving someone 10 cents or a dollar to help them get something to eat, I started buying their signs to encourage them to think of themselves as sign painters instead of panhandlers. It came to the attention of Michael Corcoran of The Austin Chronicle who did a story on it, and that started some wheels rolling. Texas Monthly came to me, and they wanted to carry on the story.

What made it so interesting is that when I first started collecting the signs, I really felt like the people who were selling were truly homeless and needed help. Then guys would say, “Oh no, I can’t sell you this sign.” I’d say, “What do you mean, you can’t?” He’d say, “It doesn’t belong to me.” I asked, “You mean somebody issued you that sign?” He’d say yeah, and I discovered that a syndicate was going around town and taking the best corners and kicking the homeless out and installing people that they hired for a dollar an hour or something. Good old American capitalism in its most greedy form.

Then I ran into a homeless guy who helped with the Salvation Army, and he would notice that some people’s signs didn’t work. He started writing slogans and sending them all over the United States on the fax machine from the Salvation Army. When I was on the road in Boston, I’d see the same signs that I’d see in Phoenix and became curious about that.

One guy had a really interesting sign and I offered to buy it. I offered him $10, $20, and he said no. I said, “What would it take to buy that sign?” He said, “You don’t understand. I made $180 with this sign yesterday.”

All of that became really curious for me. I got disgruntled on the whole thing when I found out that people were kicking people out of their spots and taking over their corners.