Spying on Canal Street

The Sheraton New Orleans now features photographer Jack Robinson's pictures of his Canal Street in the 1950s.

The Sheraton now features photographer Jack Robinson's pictures of his Canal Street in the 1950s.

Before the Marriott was built, Jack Robinson could have sat in his sixth floor office in a building that sat on that plot of land on Canal Street and looked down to where a show of his photos is now on display on the front windows of the Sheraton New Orleans. When he was in his 20s and lived in New Orleans, he was best known as a graphic artist working for an ad agency, but on his own time he started develop his photographic skills with his Rolleiflex camera. Those talents would eventually take him to New York City, where he would become a prominent fashion photographer shooting for Vogue among other magazines. "Jack Robinson's 1950s New Orleans," the show now on display at Sheraton, shows him developing his photographic voice.

Historian Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman has curated the show, which can be seen by passersby on Canal Street as well as those in the Sheraton's lobby. It will be on display for the foreseeable future, and there are plans to expand it into other parts of the hotel as renovations free up the necessary wall space. Wilkerson-Freeman looks forward to hanging a series Robinson shot in Ella Brennan's kitchen including one of Louis Armstrong performing for a television show outside the restaurant because as a black man, he couldn't legally be inside.

Most of the works selected for the lobby and the front of the hotel tell a different story. "I would call them street portraits because it's as much the street as the character in the environment," Wilkerson-Freeman says. In a brochure available in the Sheraton's lobby, she wrote, "His street portraits captured a visually rich world of nineteenth-century architecture and modern skyscrapers, settings for such Korean War-era homefront scenes as the return or departure of a soldier."

These black and white photos shot on and near Canal Street depict people in mercantile contexts - window shopping, or part of those hustling along busy downtown streets. His shots capture a New Orleans that in most cases isn't there anymore, while creating a subtle drama as the subjects in his photos are often shadowed, partly obscured, or facing away from him. When his subject is facing him, he or she rarely seems cognizant of Robinson's camera, which gives these photos a stalker-like quality - an assessment Wilkerson-Freeman agrees with in some contexts.

"That was his style," she says. "He saw elegant moments. There was elegance in his treatment of strangers."

While his photos demonstrate a clear, adventurous sense of composition with forms and light, they were also largely improvised. In a photo that's not on display, he photographed down the sidewalk at a woman window shopping in the distance, and the resulting image is all about then-modern urban existence, including reflections of other businesses in the store's big windows, and intricate fire escape shadows cast across the sidewalk. Moments after shooting that image, two African-American women walked by him, prompting him to quickly follow them, move closer to the window shopper and shoot the less design-oriented image that is on display in the Sheraton's lobby.

By Jack Robinson. Courtesy of Jack Robinson Archives.

"These photos hold many secrets," Freeman says, and she has been trying to solve them since she learned about the photos. She began studying Robinson's work when she was putting together a course on the history of the Mississippi Delta for Arkansas State University. At roughly the same time, Memphis-based art entrepreneur Dan Oppenheimer opened a gallery based on Robinson's photographs. Oppenheimer had employed Robinson in his later years after he left New York, and Robinson made Oppenheimer his heir when he died in 1997 at age 69. Among Robinson's effects, Oppenheimer found almost 150,000 negatives, many of which were unseen images of such stars as Joni Mitchell, Clint Eastwood, Tina Turner and Warren Beatty.

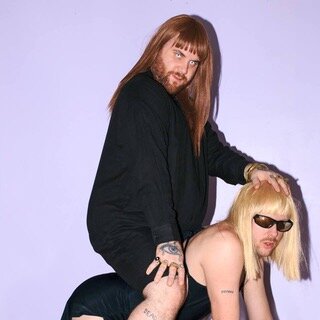

Those photos were news to Oppenheimer, who employed Robinson as a stained glass designer and knew nothing of his background in photography. "Then there were these other photographs of New Orleans from the '50s," Wilkerson-Freeman says. "They weren't Warren Beatty, they weren't The Who, they weren't Andy Warhol." Since they lacked star power, they were placed back in the box, but Oppenheimer put two of Robinson's Mardi Gras photos in the gallery, one being the photo on display in the Sheraton of the drag queens on the car. "I saw that and said, 'This is a side of the 1950s South that needs more attention.'"

A year and a half later, Wilkerson-Freeman got the time to go through the negatives and investigate Robinson's photography career in New Orleans. "When I discovered the [photo of the] nuns - because it's so beautiful - I actually started crying," she says. "I realized that I was going to have to do something with these, get them out into the world."

"I'm used to working with documents," she says. Since there was no documentation to accompany the negatives, Wilkerson-Freeman had to work from visual evidence, public records and interviews with contemporaries including artist George Dunbar to understand what and who she was looking at. She had to match architectural details in Robinson's photos to historical photos and existing buildings to situate many of the photos, and by doing so she came to understand that collectively, they documented the vitality of his Canal Street, which ranged from the Joy Theater to Magazine Street.

The challenge often led to revealing stories about the city and the times. One of Robinson's photos is of a nightclub names the Sugar Bowl, but since there were two Sugar Bowls, she had to figure out which was depicted. As she investigated the names on the marquee, she learned about Ernestine "Tiny" Davis and her Hell Divers. "They were a mixed-race, all-female group," she says. "When they came south, the light and white women in the group put on black face so they wouldn't be arrested. Every now and then, it didn't work. She came here in 1949."

The images on one wall of the Sheraton lobby demonstrate that there was more to Robinson's world than Canal Street. It is dominated by photos of Mardi Gras, and includes maskers dressed as Picasso paintings, Zulu royalty in a moment of semi-modernization, and Clay Shaw, who was charged and acquitted in connection with the assassination of President Kennedy, in costume outside Dixie's Bar of Music.

In these photos and Robinson's New Orleans work in general, Wilkerson-Freeman sees the first flickers of social progress. "There's a feeling of change going on when it comes to race and sexuality and gender issues," she says. "And also creativity. A liberation going on in the midst of the conservatism of the McCarthy Era."

For more of Robinson's work including his celebrity photos, visit the Robinson Archive. For more on the images in the Sheraton, visit Jack Robinson's 1950 New Orleans.