"Strange Stars" Tracks Sci Fi's Infiltration of Rock in the '70s

Writer Jeff Heller goes through the music of a decade to see how science fiction shaped it.

According to writer Jason Heller, “Most science fiction music of the ‘70s wasn’t reacting to the science fiction literature that was happening that moment. There was a little bit of an echo. It’s really by the mid-‘70s that a lot of the musicians stopped relying on the Golden Age authors from the ‘50s and early ‘60s.” That observation points to the most interesting parts of Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded, the book Heller wrote about the decade when rock ’n’ roll and science fiction interacted as never before. His sprawling exploration of how and why musicians employed the language, imagery, and sound of science fiction is most effective when he addresses how the genre fit into the imagination of youth culture, and what it represented in that space.

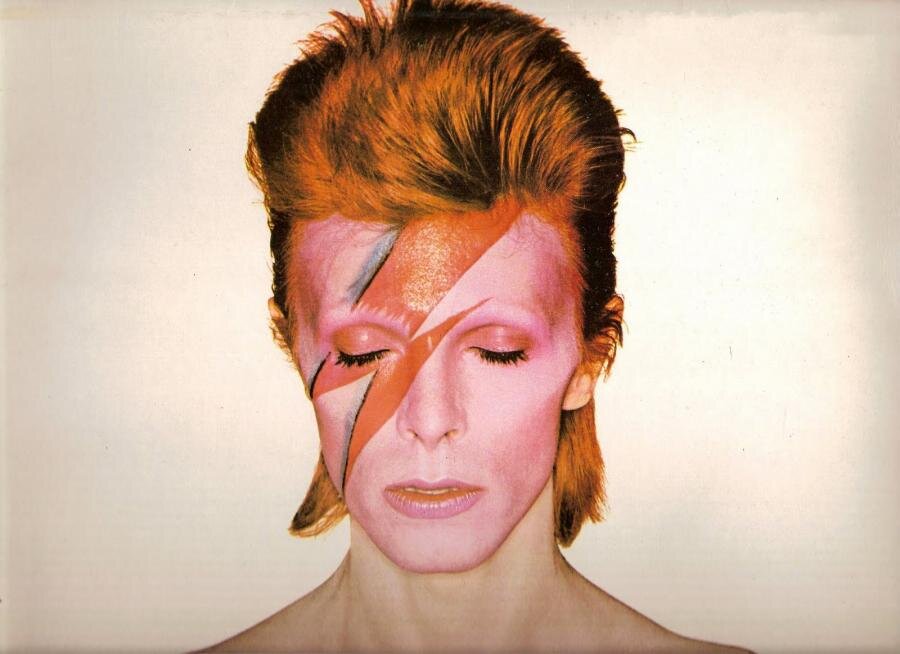

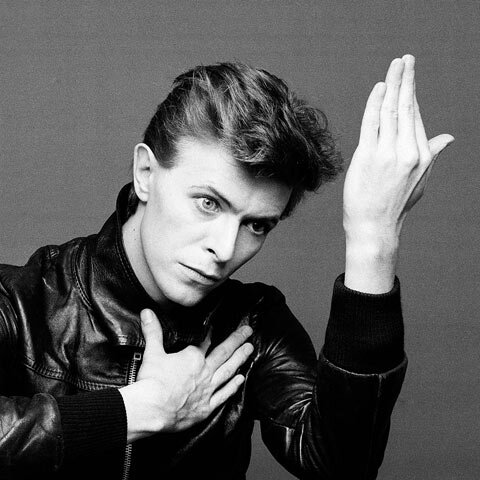

Heller will be in New Orleans to do a book signing and an in-store conversation with Michael Patrick Welch at Octavia Books on Saturday at 6 p.m. The book tracks the way science fiction entered and shaped popular music, with canary in the zeitgeist coalmine David Bowie giving the book its start and finish. Bowie’s “Space Oddity” was so well-timed to the excitement generated by space exploration that it came out a week before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in 1969. His song didn’t share the optimism in the air though, ending as it does with Major Tom lost and alone in space. When he sang, “Ashes to ashes / funk to funky / we know Major Tom’s a junkie / strung out in heaven’s high / hitting an all-time low” in 1980’s “Ashes to Ashes,” Bowie again caught the mood with space travel and those associated with it cast aside as America looked for new frontiers it could successfully explore.

“I was wrapping up the ’70s really for myself, and that seemed a good enough epitaph for it,” Bowie said in an interview. “We’ve lost [Major Tom], he’s out there somewhere, and that’s where we’ll leave him.” Still, Heller documents how Bowie couldn’t entirely close that door as he worked personally on the video for the song using a digital computer graphics workstation that wouldn’t be available for another year to render the concept as something otherworldly.

“It was supposed to be the archetypal 1980s idea of the futuristic colony that had been founded by an earthling, and in that particular sequence, the idea was for the earthling to be pumping out himself and to be having pumped into him something organic,” Bowie said. “So there was a very strong [H.R.] Giger influence there: the organic meets hi-tech.”

It’s clear that the music journalist and science fiction author in Heller are having the most fun when he can dig into stories like this one—cases where musicians talked at length about the science fiction influences behind their output. In the case of someone who could seem as dilettante-like as Bowie did at times, Heller’s deep dive is a public service as it becomes easier to see Bowie’s interest in science fiction as coherent and considered. Still, following his research in that methodical way led Heller to spend far more time with Jefferson Airplane and Starship albums than anybody but diehards asked for. Paul Kantner is a science fiction fan who spoke at length with interviewers about the science fiction underpinnings of his work starting with Blows Against the Empire, but we don’t get any insight into Starship or a reason to revisit those albums from that material.

Some bands bought into science fiction as overtly as Paul Kantner, and while it worked for their cred with critics, neither Hawkwind or Blue Öyster Cult translated their love of science fiction in enduring mainstream success. In fact, their commitment to science fiction likely marginalized them. In retrospect, it seems clear that the trappings of science fiction and what they said about artists and the fans who loved them carried more currency than science fiction itself. The way science fiction imagery located musicians on the cusp between today and tomorrow, and the possible and the plausible makes them larger than life space, which is really the way we like our rock stars.

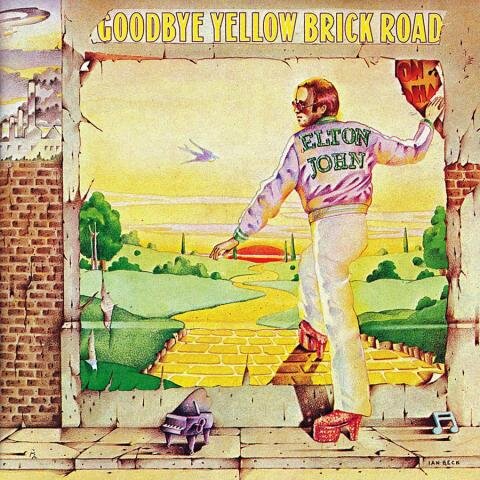

As Heller’s catalogue-like, chronological tour through the decade shows, science fiction connected artists to the cutting edge. The language fits even an austere heavy metal like UFO into the zeitgeist on the strength of its name and instrumental “Unidentified Flying Object.” Science fiction fueled the style and sound of the entire glam rock movement—not just Bowie but The Sweet, Roxy Music, and T. Rex, whose Hobbit-derived imagery matched with Dylan-esque stream of consciousness and a crunchy guitar riffs made Marc Bolan a star. In the decade that made a best seller of Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods, all signifiers of the future carried real currency, be they lyrical or musical. The opening synth blasts of Rush’s “2112” signal the band's fascination with the future as clearly as its plot and the priests of the Temple of Syrinx.

After the success of the movie Star Wars, Heller shows how science fiction as a concept had moved from an underground way to signal cutting edge cool to a mainstream marketing strategy, and that bands could reach and/or exploit the audience the movie reached. Shiny space suits, laser-like synths, and outer space window dressing helped disco acts Boney M., Meco, and Sarah Brightman reach the charts. Devo and Suicide evoked a darker future with their tech-intensive, industrial sound that anticipated the world we would see in Blade Runner by seven or so years, but they were outliers in a moment when the future in space was populated by such fresh faces as Mark Hammill, Carrie Fisher and Harrison Ford.

The irony is that, as Heller says, while science fiction signaled an artist’s place as a vanguard figure, it was a dated science fiction that had the most currency. It wasn’t until the late ‘70s when punk bands’ interest in Philip K. Dick and J.G. Ballard introduced unstable identities and dystopian futures to the vocabulary of the day. Before that, only the science fiction that found its way into popular culture through pop music had waited for its invitation into the culture for almost 20 years. Science fiction came to be seen as part of the modern condition, but for science fiction fans, it was already the past.

For my interview with Jason Heller, see TheNewOrleansAdvocate.com.