Behind Big Star's "Third"

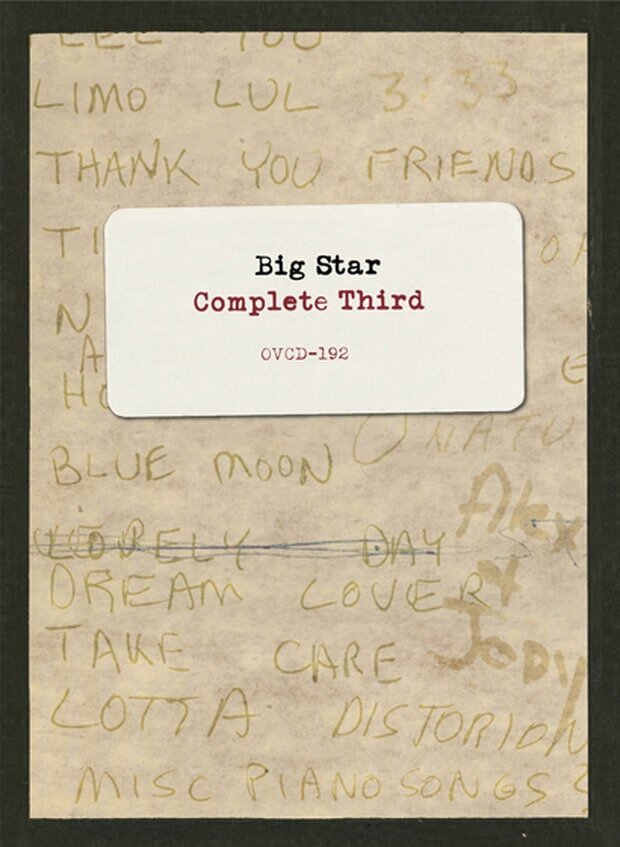

"Complete Third" presents the sessions for Big Star's troubled album from start to finish, revealing the personal, social, and musical impulses that shaped it.

Big Star’s Third—or Sister Lovers if you prefer—is the Rosetta Stone of mope rock. It’s not purely mopey, but it's hard to imagine Elliot Smith, Wilco’s more fragile moments, any of the artists beloved by NPR’s “All Songs Considered,” or all of their sad progeny existing without it. The album has always existed in a shimmering, mirage-like state, though, with every version of the 1978 release slightly different than the one before--different titles, different cover art, different running order, and even different songs. It’s not even clear that Third is a Big Star album since Alex Chilton and drummer Jody Stephens were the only members on the “sessions”—after-hours parties thrown by Chilton in Ardent Studios after Memphis’ hip bars had closed for the night. The resulting body of songs not only tells the story but successfully conveys the feeling of having your life come apart, not apocalyptically all at once but bit by bit, with moments of beauty and short-lived victories that give way to loss and sadness. Happiness isn't to be trusted on Third, and when Alex Chilton thanks his friends "who made it all so probable," in the upbeat "Thank You Friends," "probable" tumbles out of his mouth with a pronounced sneer.

Third’s ephemeral nature has imbued the album with talismanic properties, and while #1 Album and Radio City are more fun, Paul Westerberg had to be thinking of Third when he sang, “I never traveled far / without a little Big Star.” Its shambling, woozy sound make it an album that gives up its charms and secrets slowly, an album you can live with that will still whisper new sweet nothings in your ear after a decade of listens. That makes the new Complete Third one of the rare three-disc box sets dedicated to a single album that merits listening to from end to end. You can cherry pick it at your own discretion, but the set tells a coherent story as it follows the album from Chilton’s acoustic demos through band demos and early mixes by producer Jim Dickinson, to all the songs worked to conclusion during the sessions.

The first CD is dominated by Chilton’s acoustic sketches of the songs, and they show how most of the songs started in conventional, beautiful places. They connect Third to Chilton’s signature ballads on #1 Record, “13” and “Ballad of El Goodo” as his 12-string guitar shimmers and he sings with earnest, confused vulnerability. Most of the songs were already formed by the time he recorded the demos, but the box set includes “Like St. Joan”—eventually “Kanga Roo”—with a guitar part that still challenged Chilton. “Lovely Day" was in a lumpen state when Chilton cut its demo—nowhere near as rhythmically engaged--and only its signature descending guitar riff identifies it on first listen.

Still, you can hear hints of what Third will become in some of the demos. Each version of “Big Black Car” radiates bleakness, and not only because of its title image and the existentially mournful line “It ain’t gonna last.” Chilton sang it at what sounds like the bottom of his range, so he struggled to stay on key at times, and with the song as slow as it is, holding those notes tested him. Their deterioration adds to the song’s drama from the start, and the demos paired his acoustic guitar with an electric one that, like his voice, tugged at the threads that threaten to pull apart everything pretty about the song. “Downs” started as a sketchy guitar riff—barely enough to hang a pedestrian blues song on, much less the word salad Chilton came up with. It points toward Like Flies on Sherbert, but by the time Third was finished, the riff had been deemphasized, with piano and steel drums assuming the clattering, chaotic lead.

You can guess at the environment in which Chilton recorded the songs when you hear his wobbly duets with girlfriend Lesa Aldridge on The Beatles’ “I’m So Tired” and Gram Parsons’ “That’s All it Took,” the latter with a band at its most rudimentary. When Chilton got to the solo, he broke off a deliberately primitive guitar break that threatened the integrity of every string he touched. You come away with the impression he was playing with Aldridge, for her, and whoever else was still up and ready for one more drink. A portion of “Pre-Downs” became the introduction to “Downs," but by itself it's five patience-testing minutes of people badgering their instruments. Covers allowed others to get in on the act. Aldridge sang The Velvet Underground’s “After-Hours,” and seemingly everybody who came by after last call played a part on Chilton's ramshackle take on “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.”

In those tracks and the demos, you can hear a guy profoundly cynical toward the whole rock music enterprise. Holly George-Warren’s A Man Called Destruction tells the story of Chilton who was, by the early ‘70s, sideways with the music business and his talent. When he was 16, he sang someone else’s songs with husky voice of a blues belter in The Box Tops, and he was loved. He sang his own songs in his own voice with Big Star and couldn’t get his records into stores. Critics loved them but buyers couldn’t get them because of distribution issues. Combine that with seeing too much of the world at too young an age, and you can easily imagine someone unable to take conventional, pristine pop seriously.

His ambivalence about the value of beautiful music shows up more clearly in Dickinson’s mixes when the songs started moving closer to their final forms. Chilton instructs at the start of a version of “Take Care,” “Let’s start with just a verse of me playing guitar and everybody fooling around, and we’ll save that for some kind of juicy little instrument later. So y’all fall in.” That instruction produces the familiar loose, ambient contributions that ominously suggests the rising storm he’s worried about will come sooner than he thinks. A rough mix of “Holocaust” has a low, didgeridoo-like held note that singlehandedly makes the version claustrophobic.

According to Bud Scoppa’s liner notes, Ardent Studios’ owner John Fry didn’t understand gestures like those or Chilton’s direction and tried to coax him to adopt a more conventional approach. That tug of war is evident when Fry’s rough mix of “Nighttime” comes six tracks after one by Dickinson. The tape itself sounds like it needs to catch a cab home on Dickinson’s mix, and Chilton’s acoustic guitar is little more than a textural element on a track defined by Chilton’s voice, a slide guitar, and a tambourine played with the freedom of a lead instrument. When Fry got the song—and almost any song he touched—he brought Chilton’s 12-string to the foreground, reduced the prominence of the tambourine and 86’ed the haunted slide parts. The songs are more reliably entertaining, but they lack the loose musicality of the tracks Dickinson mixed. He wasn’t deaf to what Chilton was doing as Fry’s mix of “Kizza Me” demonstrates, but more often than not he tamped down the madness.

If the world had ended up with many of the rough mixes, Third would still have found its cult. The Chilton-sung take of “For You” lacks the ineffable honesty of the final version sung by Jody Stephens, but it’s really beautiful. An alternate version of “Take Care” sounds like it was sung the night Todd Rundgren’s carnival burned down, and Dickinson’s rough mix of “Kanga Roo” would still be one of the best-loved songs on the album with a slightly more dynamic relationship between the instruments, including a Mellotron.

Because the songs were still very much in process during these mixes, these rough mixes aren’t only for completists, obsessives and scholars able to recognize microtonal differences. We can hear the tensions as Dickinson and Fry tried to make sense of Chilton’s personal/social recording process, which gives Complete Third genuine drama. Big aesthetic battles play out before our ears, and it’s easy to root for Dickinson’s mixes and Chilton’s more personal vision. When you hear Fry’s mixes though, his confusion makes sense. Why is Alex fucking up all these beautiful songs? When you get to the final versions, they’re not redundant.

As for the official release of Third, plenty has already been written. Critic Robert Christgau covered the basics when he wrote:

In late 1974, Alex Chilton--already the inventor of self-conscious power pop--transmogrified himself into some hybrid of Lou Reed (circa The Velvet Underground and/or Berlin) and Michael Brown (circa "Walk Away, Renee" and "Pretty Ballerina"). This is the album that resulted--fourteen songs in all, only two or three of which wander off into the psycho ward. Halting, depressive, eccentrically shaped, it will seem completely beyond the pale to those who already find his regular stuff weird. I think it's prophetically idiosyncratic and breathtakingly lyrical.

On Complete Big Star Third, the album in its final form is the necessary end of the story, but it’s hard to imagine who’d start listening to the set at all without knowing already knowing how it ends. That said, Third still satisfies, even after a couple of hours spent listening to how it came to be.

The word “complete” in Complete Third doesn’t mean it’s the definitive word on the album, though. At one point Fry had seen and heard enough of Chilton’s experimental, improvisational recordings and decided that if he didn’t declare the sessions done, they never would be. He gave the tapes to Dickinson, who completed them in good faith, though Chilton is quoted in the liner notes as saying that he would have made many choices differently than Dickinson did. It was Fry who put the name Big Star on the project thinking that it had more market value than Chilton’s, and because Chilton wasn’t a part of the album’s completion, it’s hard to know what he would have made from all those tracks. Complete Big Star Third doesn’t shed much light on that mystery, but it does as good a job as any box set of helping us understand how any album is made, and certainly one as complex and troubled as Third.