"Thank You Friends" Stabilizes Big Star's "Third"

The album that inspired a cult following with its layers of actual and ephemeral haze feels more solid when filmed and recorded live.

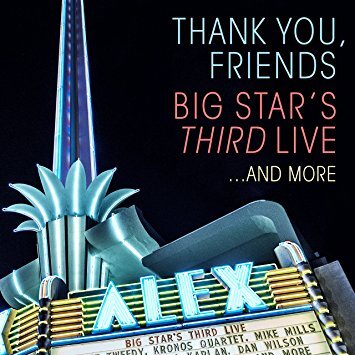

You can see how much Big Star meant to a generation of musicians on Thank You Friends: Big Star’s Third Live … and More. Members of Wilco, Yo La Tango, R.E.M., The dB’s, The Kronos Quartet and more united last year at the Alex Theatre (really!) in Glendale, California to play the band’s dark, ephemeral masterpiece, and their love of the material is obvious in the performances captured on this two-CD/one-DVD set. The core band assembled by Chris Stamey has taken the show around the country where other Big Star and Alex Chilton fans have sat in including Michael Stipe, Ray Davies, Aimee Mann, and Van Dyke Parks.

The band’s first three albums—#1 Record, Radio City, and Third (alternately known as Sister Lovers)—inspire such reverence in their admirers that for all the talent assembled onstage, the versions are all remarkably faithful to the 1974 recordings. Yo La Tengo’s Ira Kaplan reaches for a deeper fragility than Chilton could reach on “Take Care” and Robyn Hitchcock is very Hitchcock-like on “Downs,” but few liberties are taken with the source material. That’s likely a practical decision as the 12-piece band, horn section, and The Kronos Quartet had to learn 30 or so songs, and faithful versions make that easier. Still, when a scheduled Big Star show at SXSW turned into a Chilton tribute when he died in the days before the show in 2010, the performances were similarly faithful. It’s one of the many ironies attached to the Chilton/Big Star story is that he and the songs inspire such reverence despite his own irreverence and disinterest in playing a song that he couldn’t imprint with his own voice.

I’ve always believed that the mythic status of those first three Big Star albums grew from the way the album as initially released on vinyl played into so many rock ’n’ roll narratives. They were released on Ardent and distributed by Columbia as part of Columbia’s distribution deal with Stax Records. Stax’s financial troubles prompted Columbia to squeeze its releases, so while critics got and reviewed promotional copies that they raved over, buyers couldn’t find them then and had to hunt for them in used record stores for the next decade or so. That gave each copy a talismanic quality, and each time you found one felt miraculous. I never found Radio City on vinyl, so I speak from experience.

The musicians in Thank You Friends tell their stories of finding Big Star albums, and they’re remarkably similar. Someone turned them on to a Big Star album and that was it. They heard their musical future in that moment, which is another cherished rock ’n’ roll trope. What they heard in Big Star was a band that found the logical American extension of The Beatles by making pop and rock ’n’ roll that took the counterculture as a given without celebrating it. At the same time, Big Star gave the music sense of place that merged Liverpool and Memphis into a distinct place that wasn’t exactly anywhere. Radio City pointed clearly to indie rock, which may explain why Big Star’s cult is unified by an age demographic. The album pointed to a sound that independent bands started picking up on by the mid-‘80s and would codify over the course of a decade, so it didn’t sound as forward thinking a decade later.

Third sits next to the first two Big Star albums the way John Lennon solo albums existed next to The Beatles, and for that reason (among others), some think of the album as a mislabeled Chilton solo album more than a Big Star album. Drummer Jody Stephens is the only other band member to play on its sessions, which acquired their own mythic status for ramshackle beauty and chaos, and he considers it a Big Star album. He plays drums on Thank You Friends and is the last living member of the band, which lost Chris Bell in 1978, and Chilton and Andy Hummel in 2010.

Stephens still works at Ardent Studios, where he is Business Development Director. His Big Star adventure began when Andy Hummel introduced him to Chris Bell and the trio started writing and recording songs at Ardent under the supervision of producer and studio owner John Fry. Because Big Star existed largely in the studio, rarely played live and didn’t tour, I’ve always wondered if it was ever really a band. The differences in the band’s sound from album to album fuel that suspicion but Stephens believes it was.

“There was such a bond among the four of us musically,” he says. At the time though, particularly early on, Stephens’ associations with Big Star were all about playing and finding people with whom he could make music that inspired and satisfied him. “Being in Memphis and being 15, 16, 17, the prospect of being in a successful band seemed like a pie in the sky thing.”

Stephens’ take is completely rational—something rock ’n’ roll rarely is. On #1 Record, you can hear the excitement and the barely guarded optimism that maybe, just maybe, a musical world could open up for the band, even though the odds against the band were lottery-like. Memphis was a Stax and Sun city to the extent that it had a music industry, and even though there were a few fellow pop travelers, the dominant musical styles were blues and American roots music, not psychedelic power pop.

Spoiler alert: Big Star didn’t find its audience at the time, and Chris Bell didn’t handle that well. He began to suffer from depression and left the band within months of #1 Record’s ill-fated release. Chilton, Hummel and Stephens continued and made Radio City, then Chilton and Stephens were the last men standing for Third. Despite that, Stephens says, “Alex was never somebody I could sit down with and feel perfectly at ease with in a conversation as friends.” In the studio working on music, Stephens felt perfectly comfortable with Chilton, but he too felt the spikiness that almost anybody who dealt with Chilton eventually experienced. At the time, their Chilton’s love of downers and didn’t help.

“Both of those things make life pretty dramatic,” Stephens says. “Unless you dive into that drama along with everybody else, I don’t know anybody who has fun with it.” Because Stephens didn’t do drugs himself and had to either work or go to school most mornings, “I guess I managed to miss a lot of it,” he says.

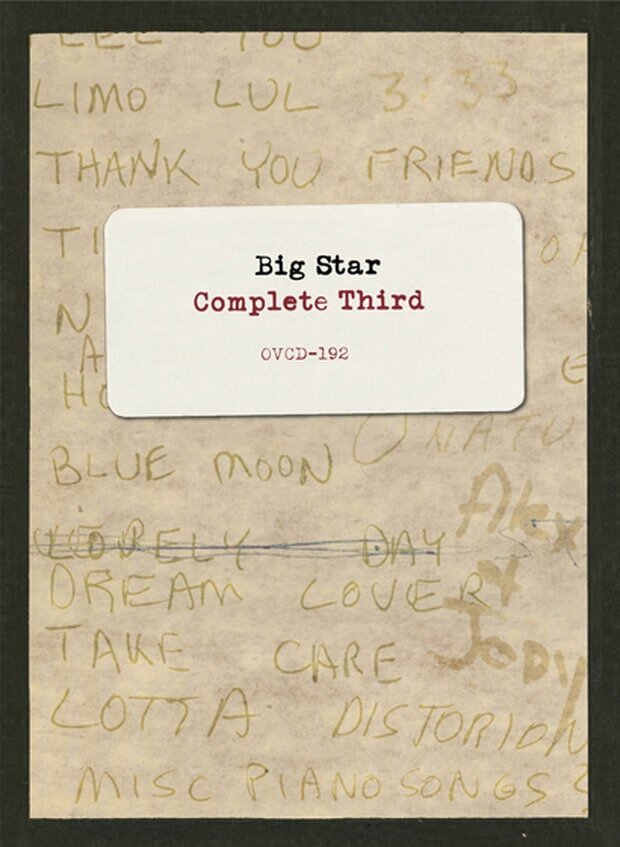

The liner notes for last year’s Complete Third box set tell the story of Chilton leading crazy, drunken, late night recording sessions with whoever he’d been drinking with earlier that night. There’s clear evidence to back up those stories on Complete Third, but Stephens remembers more conventional sessions during the day at Ardent Studios as well. “There could have been later night things that went on, but they weren’t chaotic when I was there,” Stephens says. “But I wasn’t a late night person.”

He remembers one point when Chilton went in the studio to sing, “Neeet neeet neeet,” which seemed inexplicable until house producer and engineer John Fry mixed the part into the song. “I didn’t really have a sense of where [the album] was going, but when I stepped into the control room and parts were added and John did mixes, I could hear it coming together. John was a brilliant mix engineer. He intuitively knew where to place things in a mix and help shape the sonic picture through his mixes.”

The album’s legend and the late night sessions seemed to favor spontaneity, but Stephens remembers Chilton’s musicality as well. “Alex’s delivery on an acoustic guitar was a complete performance,” he says. “His guitar performances were also so emotive. If you wanted to build something around it, you could, but you had to be careful to stay true to the spirit of that guitar and vocal not to mess it up.”

Stephens’ account of Third is often at odds with the stories told by Bud Scoppa in the Complete Third liner notes and Holly George-Warren in her Chilton biography, A Man Called Destruction. George-Warren’s interviews led her to see Chilton and producer Jim Dickinson as working together to go to a less more experimental musical place, while Stephens gives Dickinson more of the agency. “Jim took it a little farther out in space,” he says. “But it’s amazing how it all came together when John was mixing.”

Those conflicting accounts feel quintessentially rock ’n’ roll as well with everybody telling the story unreliable at some level. The unstable story is apropos for Third, an album that has historically seemed unstable as well. It has been released with different covers, song lists and running orders, and because Fry eventually took the project away from Chilton before he flew it into the side of a mountain, the one person who might have known didn’t have a say.

Thank You Friends gives Third a little more solidity, and for Stephens the experience can be emotional, particularly when he’s rehearsing on his own to the original tracks. “I’ve got a bootleg performance of Big Star 2 and I’ll play along with that performance, and I hear Alex talk in between songs and—wow,” he says. “Oddly enough, playing it live is such a joyful experience even though some of the material is pretty dark on the third album.”