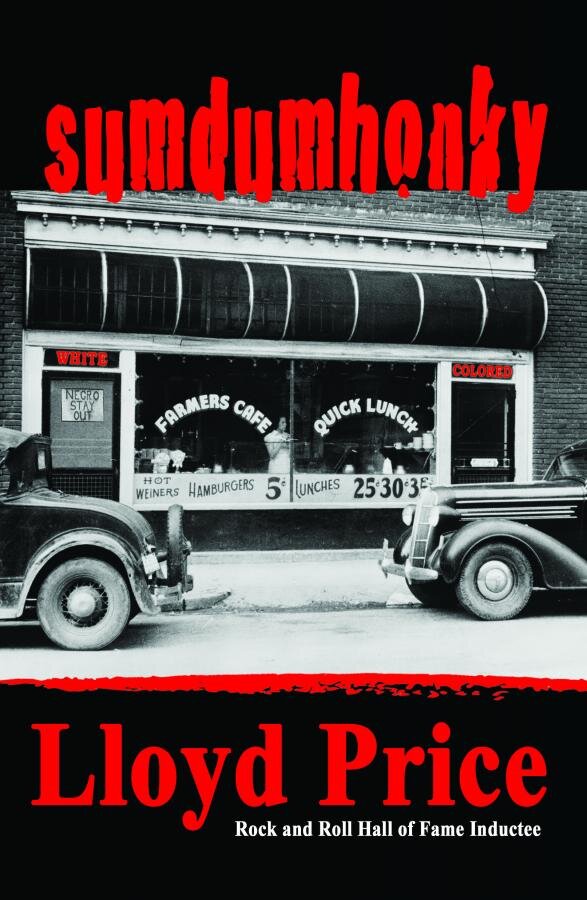

Lloyd Price Tells the Story of "Sumdumhonky"

The Rock and Roll Hall of Famer remembers growing up in Kenner and dealing with racism.

In the year of #blacklivesmatter, Lloyd Price’s new book Sumdumhonky is a useful addition the body of black thought. Price, the singer who had hits with “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” “Personality” and “Stagger Lee,” is short on insights of his own, but he documents a way of thinking that started when he was a kid growing up in Kenner. Like so many of his generation, Price grew up the 1930s and ‘40s feeling the constraints of white authority. Price felt it directly from “Ol’ Jake”—a stuttering racist cop—growing up, but Ol’ Jake became a symbol in the book of all ignorant, unjust, unwarranted white power over his life.

Price’s writing is more revealing than it is insightful. He doesn’t have much new to say about racism, but a lifetime spent experiencing it hasn’t muted his outrage. He repeatedly wonders why people felt like they could treat him as if he wasn’t human, and returns to the questions he has never got satisfactory answers to over the course of his life. All those “why”s connected to racism read like a trap in Sumdumhonky, as Price goes through a maze of his own devising trying to work out the logic behind illogical attitudes. The satisfying answers he wanted don’t exist. Because of that, Sumdumhonky can be frustrating, but not as frustrating as living with the racist experiences that inspired the book.

Price so routinely outsmarts or gets the better of his racist oppressors that it’s hard to take Sumdumhonky at face value—an impression furthered by the inexplicable pull quotes inserted in the pages that come not from the text but from general endorsements of Price as one of the pioneers of rock ’n’ roll written in magazines and papers. Still, Price’s writing seems emotionally real. He moves episodically through his life, achieves some understanding, and develops defensive strategies along the way. The account of his trip to Nigeria was particularly important because it taught him that although his people come from Africa, he is a black American.

Conventional wisdom right now says that the fight against racism in 2015 is the fight against institutionalized racism—systems of oppression—more than the Ol’ Jakes of the world. The Ol’ Jakes are still out there though, as the Charleston shooting made clear. They may not be stuttering or slack-jawed, but active, individual hostility toward African Americans is very much alive. Anyone who believes that the racially disproportionate arrests in Ferguson happen without at least some personally, deliberately racist cops doesn’t want to believe the truth. With that backdrop, Sumdumhonky is valuable on a number of levels.

Price lays out in painful detail the sense of being trapped that racism fosters. He also spells out the mindset that grandfathers passed along to their children who passed it on to their children. Why do African Americans see racism in such initiatives as efforts to further regulate voting? Because they’re used to seeing white America do what it can to minimize black power and autonomy. You can argue with the accuracy of their perceptions, but not their emotional realities. Sumdumhonky is most effective as an account of what it felt like to grow up black.