The Clash vs. The Clash

"The Rise and Fall of The Clash" details the fall more than the rise of "the only band that matters."

Director Danny Garcia’s The Rise and Fall of The Clash is more of a VH-1, “Behind the Music”-like TV documentary than a genuine examination of the band’s birth and death. It does get at the central tension between Mick Jones and Joe Strummer’s sensibilities and how that ultimately contributed to the band’s collapse, but the focus is far more on how the band fell apart than how it came together.

For the film, Garcia interviewed a lot of people in the band’s orbit, and all the members show up in the film though only Jones was interviewed specifically for it. As a result, the documentary comes down particularly hard on manager Bernie Rhodes, then on Strummer, who listened to him and sided with Rhodes against Jones. Rhodes was around for the formation of the band, but he was sacked in 1978. During the time of London Calling and Sandinista!, The Clash were managed by the decidedly un-punk Blackhill Enterprises, whose Peter Jenner and Andrew King had also managed Pink Floyd and T. Rex. The Rise and Fall of The Clash’s narrative becomes more detailed when Rhodes returned as manager in 1981 at Strummer’s behest to help the band re-find its political and personal edge.

In Garcia’s telling, that immediately pitted Rhodes against Jones, who helped engineer his ouster the first time. Jones was targeted for being soft and bourgeois, and as the member with the greatest affinity for the conventional rock star life, he was an easy target. Strummer had anxieties about money and authenticity, so he was prepared to safeguard The Clash’s stance as the people’s band while taking stadium gigs in the United States and opening for The Who.

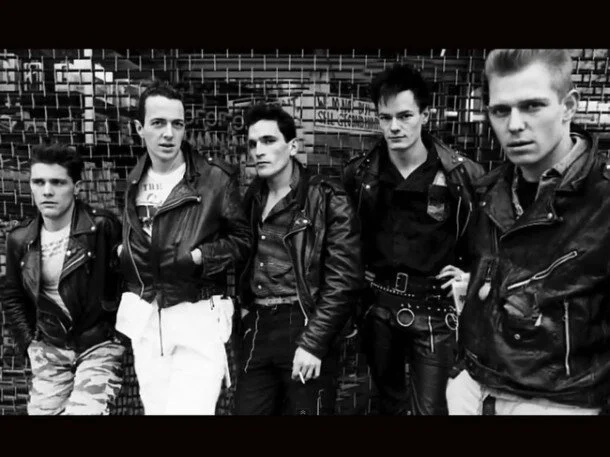

Because the story’s pretty simplistic, the documentary is suspect as gospel truth but it never feels phony and has some real charms. First, there’s a lot of very exciting footage of the band onstage from throughout the band’s career. The Clash were always stylish and visually compelling, and even the less theatrical moments onstage had great tension, whether its Jones’ agitator-like twists while playing, or the intensity with which Paul Simonon seemed to be in his own world. More importantly, Garcia’s story patiently walks through the slow trading down of band members until the band’s decline was irreparable. Anxiety over drummer Topper Headon’s heroin use led to his ouster in favor of Terry Chimes (who didn’t have a full band rehearsal before playing the first gig of an American stadium tour because Simonon was already in the States), then Chimes’ voluntary exit and the entrance of Pete Howard, who was then secretly a Yes and Genesis fan. After Jones was sacked, Strummer and Bernie Rhodes hired guitarists Nick Shepherd, formerly from punk band The Cortinas, and Vince White, who distinguished himself in a group audition by declaring, “I’m not playing this shit,” after which he was hired for his attitude.

“It was a very Bernie Rhodes thing to do,” Pete Howard says, and the substitution of non-musical values for musical ones eventually led to Cut the Crap and the end of the band. Garcia’s public service comes in his documenting of this less told last chapter of The Clash’s story.

The thought that emerges through the story is that The Clash were out of ideas - or shared ones, anyway. Jones was into hip-hop and modern sounds, while Strummer preferred to look to the past and rockabilly. At one point before Jones left, Rhodes suggested the band record an album of New Orleans music - something it had nodded to with London Calling’s “Jimmy Jazz” and Sandinista!’s “Junco Partner,” but an idea that even today sounds like a conceptual solution to a core problem of an overworked band that had lost the plot as it grew far beyond anyone's expectations. In a clip, Strummer rationalized Jones’ firing, saying the band had “work to do” without saying what that work was. Simonon pointed not to a musical impasse but to Jones’ personal schedule impeding additional touring.

In the last section, the movie catches fire with footage of a drunken, emotionally wounded Vince White and the sad Pete Howard. They're involving on camera, and two along with Shepherd were paid a pittance and put on a straight edge regime by Rhodes to artificially re-create the hunger that fueled the original lineup in the first place. With all the money that was coming in, all that did was foster bitterness and a sense of hypocrisy. The more Strummer talked about stripping thing back to punk roots, the more he inadvertently drew attention to his own financial, social and cultural distance from that time. His lectures in clips are joylessly strident, and if he was that guy in 1977, his band would never have gotten anywhere.

In the end, The Rise and Fall of The Clash contends that Rhodes saw himself as a member of the band, and that The Clash was his band. Strummer came to realize he’d been had, but the damage was done. According to the film, Strummer went to see Jones shortly after Jones had finished the first Big Audio Dynamite album, and Strummer hoped to reunite The Clash badly enough to follow Jones to Nassau and biked around the island for days trying unsuccessfully to find him. Rhodes tried to keep the band alive after Strummer called it quits.

The Clash’s story ends up being sadly common and needless in all the usual ways. When the band ran out of mountains to climb, the only thing left to overcome was each other, and once again management made a good situation worse. The irony the documentary highlights is that the thing that stopped The Clash from being the only band that mattered was The Clash.